Lost Weekend

16 Aug 2016 – 27 Aug 2016

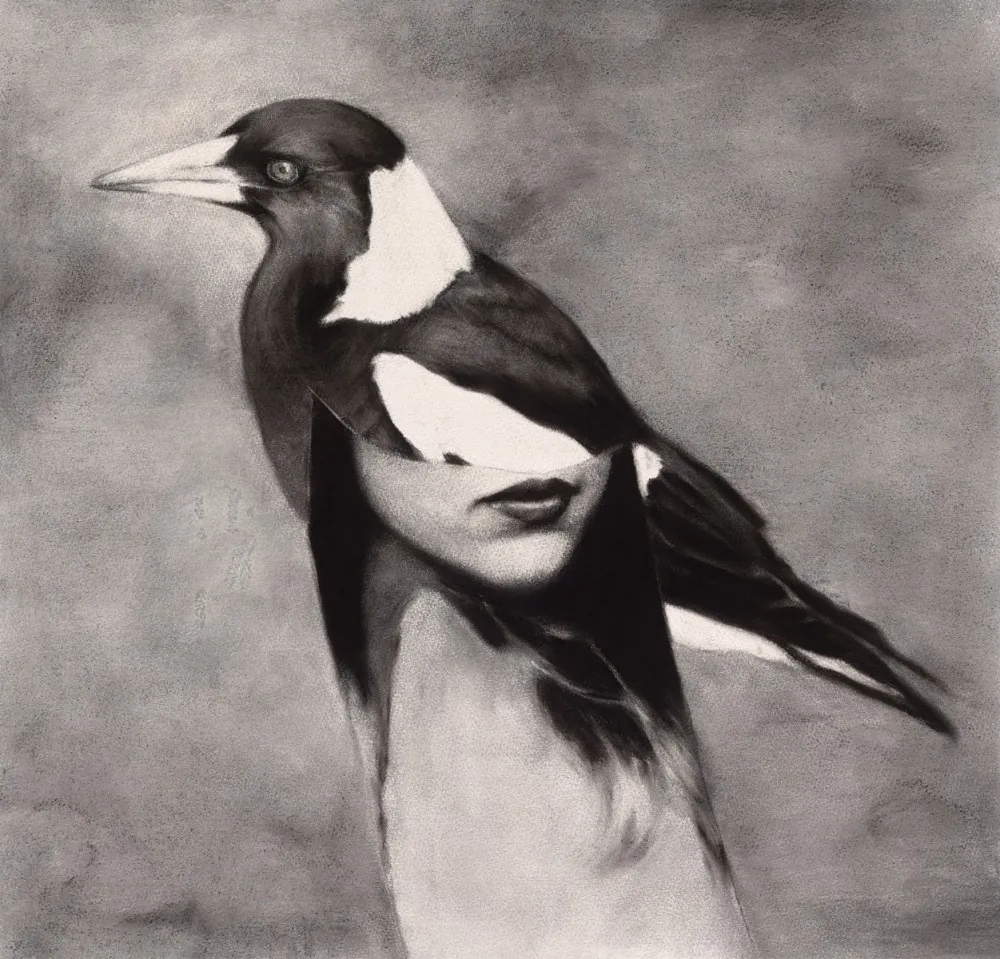

Heidi Yardley’s Cadavre Exquis

Essay by Ashley Crawford

“… the association of two, or more, apparently alien elements on a plane alien to both is the most potent ignition of poetry.”

– Comte de Lautréamont, Les Chants de Maldoror, 1869

Heidi Yardley’s latest works inspire burning questions. Her animal-human hybrids could see her feminine protagonists embracing nature with an almost bizarre passion. Alternatively these could be fashion models adorning the latest feathery and scaly accouterments. Another possibility may be that these women have suffered strange environmental mutations. One thing is without doubt; they wear their birds and lizards whilst retaining a sultry sensuality. But one wonders – are they wearing their animals or are the animals wearing them?

There have always been forms of animal-human splicing. Tribal warriors in various parts of the globe adorn themselves with feathers to inspire fear and respect and to attract the attention of women. Women, meanwhile, have adorned feathers and furs to attract the attention of men. There is a long and magical history of human/animal interface. Consider the legends of Marsyus and Pan. The Greek Centaur and the Japanese Kitsune, or Anubis, the Egyptian God of the Dead with his head that of a jackal. And then there are the more contemporaneous versions of H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau, David Cronenberg’s The Fly and Charles Burns’ Black Hole, amongst others.

Heidi Yardley’s ladies of the night are, I like to imagine, adorned to partake in a lavish party, patiently waiting for the artist to capture their likeness in charcoal, thus to be remembered in their painful but beautiful melding with the natural world. Perhaps they have gone to extremes to attend the immensely wealthy Marie-Hélène de Rothschild’s famous Surrealist Ball at Ferrières, which was held on December 12, 1972 and attended by the likes of Audrey Hepburn and Salvador Dalí. The requirements for the evening were “Black tie, long dresses & Surrealists heads.”

Yardley takes these notions of animal/human interface to new extremes, introducing an element of sheer seduction into the proceedings. There is the almost inevitably sultry glamour of the artists’ renderings of women – see By the danger in your eyes – and her embrace of a distinctly ‘retro’ style (the artist has at times utilised imagery from early 1970s porn, a time when the plumage of pubic hair was de rigueur.) Filmic sources and magazine photography have long played a role in Yardley’s work, both as a source and an inspiration. Her title, Lost Weekend, is in fact a play on the film title Long Weekend (1977), ostensibly a horror flick about nature’s revenge on a man treating the bush with contempt. By a quirk of fate the gallery’s director, Nicholas Thompson, had misread Yardley’s handwriting, interpreting “Long” for “Lost,” thus accidently, but aptly, renaming the artists’ show, much to Yardley’s delight. This was also, fittingly, a form of Cut-Up or Cadavre Exquis (Exquisite Corpse) – the collaborative poetry game that has its roots in the Parisian Surrealist Movement and involved such participants as André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Yves Tanguy, André Breton, Man Ray and Tristan Tzara. While it began as a form of Chinese Whispers with surreal word usage (later inspiring William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up method) it rapidly evolved into a more visual series of collaborations. With Yardley’s approach, with its cut-and-paste technique, in this case a montage of nature photography and fashion imagery, which is then rendered masterfully in charcoal, something not dissimilar occurs, the juxtaposing elements initially jarring until settling into a form of poetry.

Yardley has long been the master of melding beauty and threat. “This series investigates the relationship between the natural environment and the human psyche, particularly focusing on notions of fear,” she says of Lost Weekend. The allusion to the fabled Azaria drama in Shake dog shake aside, these fears are not entirely unfounded; I was once asked to travel with a Japanese artist through Australia’s centre. I had warned him about making noise to scare away snakes when undertaking his ablutions. He learnt that trick, only to find himself squatting one day over a bull ant nest. Another lesson was learnt… the hard way.

“Lurking within the common consciousness of Australian identity is a fear of dangerous wild animals and the treacherous natural environment,” says Yardley. “These hybrid images speak of connection and disconnection, primal urges, desire and fear.” Indeed, fear and beauty reside in equal measure in these works. She melds two forms of exquisite visage – the glamorous femme fatale and the exotic plumage and sensual squamous scales of Australian wildlife to create hybrid life-forms both alluring and threatening.

The sumptuous sense of nostalgic fashion photography is captured via Yardley’s almost photo-realist use of monochrome a la Max Dupain and her elegant placement of her “models” as they show off their accouterments. In The Crown this takes the form of a cockatoo’s plumage, in Serpentine our subject has adopted snake skin and in Sombre Reptiles her appurtenances take on the form of an entire lizard as facial wear. But it is with Throw me to the sky that our original speculation returns. Are they wearing the wildlife? Or is the wildlife wearing them.

– Ashley Crawford